Summertime, and the Living Is – Precarious?

This should be a straightforward column about the typical joys—and risks—of summer: cook-outs with a chance of food poisoning; beach basking with a chance of sunburn; water sports with a chance of rip tides; sparklers and fireworks….

But nothing is straightforward about summer 2020. Despite the arrival of those lazy, hazy days we know and love, we can’t escape the ever-present risk of COVID-19.

As I’m writing this, Delaware is reopening. Restaurants can expand services beyond delivery and carry-out; non-essential workers can get haircuts; people—even out-of-state visitors!—can hit the beaches. Amidst it all, we wear our masks and try to keep a six-foot distance from folks who don’t live in our households.

By the time this issue is published, we’ll know a little more about how that reopening is working out. It will have been more than two weeks since restrictions were eased; COVID-19 has about a 14-day incubation period. So: are COVID-19 test-positivity rates beginning to rise? Are the hospitals sending up flares—not to celebrate a festive fourth, but to signal an uptick in virus-related ER visits or admissions? Stay tuned.

As we navigate through this summer of our “next normal,” we need to know how we can most safely pursue some of summer’s usual delights. Because you know what? Most of us just are not going to forego every pleasure for the foreseeable future.

Not that there haven’t been efforts to encourage people to do exactly that—i.e., to just stay home. Abstain from contact. Indefinitely. Especially if one is age 65 or older, or has chronic medical conditions, or is immunocompromised.

It’s reminiscent of advice once given to stop the transmission of HIV or prevent teen pregnancy: abstinence. We all know how well that worked out. “Stay home” is not going to work forever for COVID-19, either.

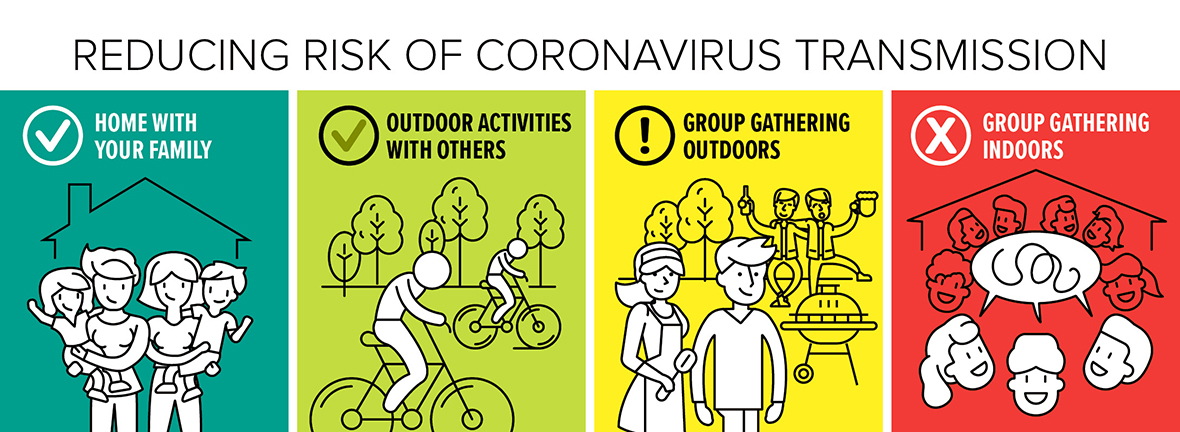

Happily, a couple epidemiologists, Julia Marcus (Harvard) and Eleanor Murray (Boston University), have identified a middle ground between the dichotomy of low risk/high safety (stay home) and high risk/low safety (densely-populated indoor gathering) options. They offer both a moderate risk option—outdoor activities—and a higher risk option—outdoor gatherings. Google “marcus covid risks chart” to see a nifty graphic outlining all four options.

Marcus and Murray also offer mitigation strategies for each level of risk. Common to all levels are the familiar ones: wash our hands, don’t touch our faces, stay at least six feet away from people we don’t live with, and wear a mask.

For outdoor activities, they advise—in addition to those basics—that we stay away from shared surfaces like swings or benches. For outdoor gatherings, they add a few more: gather infrequently, and don’t share food or toys.

Even for large indoor gatherings (the highest risk/lowest safety scenario), they have some ideas that might help. First, avoid these as much as possible. And if we simply must join a crowd indoors, open the windows.

So, how might we explore those options that lie beyond our doors, yet keep ourselves relatively safe? Well, for outdoor activities, we might:

Pursue our chosen activities only with people who live in our household.

Or, carefully select a few—v. a few dozen—folks to join us. And choose people whose risk behaviors (mask-wearing, social distancing, etc.) align with ours.

Keep our distance (from those we don’t live with) even within the group—no huddles.

Choose individual activities, e.g., tennis or golf, v. team sports like volleyball or water polo. (The water isn’t the danger—the virus won’t survive in a properly maintained pool. It’s the players who are spluttering or coughing all over us we need to avoid.)

With some forethought, we can even host an outdoor gathering: let’s have a picnic!

Keep the party small; think in terms of a household or two.

Position each household’s table or blanket six feet away from each other household’s table or blanket. (It’s OK for the host to supply the tables; each household needs to supply its own blanket.)

Ask that each household bring its own food and utensils—and, no sharing across households. Forget pot-luck or shared chips-and-dips.

Fire up the grill! One fun exception to not sharing—grilled food can be distributed across households. The cooking will destroy any virus. Serve grilled items directly onto each person’s plate.

Set up a hand-washing station. Provide hand sanitizer if we’ve found some. Position a bucket, some soap, and paper towels by an outdoor hose.

Provide trash bins outdoors so each household can dispose of its own trash—and can do so without going into the house.

By the way—we don’t need to disinfect the outdoor picnic tables or benches or Adirondack chairs: time and weather will take care of that.

Remember, it’s a picnic. Not a day of wild abandon:

No singing around the campfire. Singing spreads droplets—and the virus—widely.

Watch the alcohol intake: people become more convivial and less cautious under the influence. And they can become louder; more forceful speech can spread the virus farther than quiet speech.

Circulate: longer conversations produce more droplets (and potential virus) than shorter ones. Want to have an extended heart-to-heart with someone you don’t live with? Wear a mask. Talk across a six-foot distance. Don’t face one another directly.

Avoid contact sports—and cheering too enthusiastically. Cheering sprays droplets very effectively; contact sports—well, because, “contact.” Croquet, anyone?

Safe Hugs! What’s Not to Love?!

Now, here’s some really good news: There are people out there working to quantify the risk inherent in something we’ve been keenly missing: hugs. Linsey Marr, an aerosol scientist at Virginia Tech, is one of the world’s leading experts on airborne disease transmission. She’s been running the numbers and has concluded that the risk of exposure to the virus during a brief hug is actually pretty low. Especially if we don’t cough or talk during the hug. Marr and other experts have come up with some hugging dos and don’ts:

Don’t hug someone who is coughing or otherwise symptomatic.

Wear masks.

Avoid touching the other person’s clothing with our face or mask.

Hug outdoors.

Hug facing opposite directions—i.e., looking over one another’s shoulder—rather than face-to-face or cheek-to-cheek (facing the same direction). The idea is to avoid comingling our breath.

As we close in for the hug, don’t talk, and don’t face one another directly—look off over our intended’s shoulder.

If we really want to be careful—we should hold our breath. This is going to be a hug, not a lengthy embrace. We can do it.

Keep it short, then back off quickly. Don’t breathe in one another’s faces or speak as we step back.

Wash our hands.

Try not to cry, however joyful we feel: that just creates more fluids that may contain the virus, and increases risk as we reach to wipe away the tears.

Google “Marr hugging pandemic” to see more.

Marj Shannon is an epidemiologist and wordsmith who has devoted her life to minutiae. She reports that yes, the devils are in the details.