Prince Left an Indelible Mark on the Queer Community

As I write this, Prince died two years ago today. His life and career left an indelible mark on many different communities, for just as many reasons, including the queer community.

There’s much for a queer person not to like about Prince. Later in his career, 2008 to be exact, when he returned to the conservative faith of his childhood (Jehovah’s Witnesses), he spoke dismissively about gay marriage in religious terms, seeming to blame the “Great Flood,” which necessitated Noah’s Ark, on homosexuality—or, as he charmingly put it, “people sticking it wherever and doing it with whatever.”

And yes, Prince was certainly a fan of the female form and all nature of heterosexual couplings—but as LGBT people, we have our own reasons for remembering him fondly.

Most obviously, much earlier in his career, Prince was an avid proponent of sexuality, period. He held an unapologetic belief, evidenced in both his lyrics and his persona, that sexual desire was a part of a person’s core, that sex was natural and healthy and right—even if it’s not the kind of sexuality that society might deem “normal” or “conventional.” In many ways, Prince allowed people to explore their own inner sexual lives. His music was hot, steamy, and sensual, and served as a celebration of carnal desire.

Prince’s love of sexuality extended beyond his words and became part of his person. He created a look that included elements of the feminine, and during the first peak of his successful career, shared the world stage with artists such as Madonna, Grace Jones, Boy George, and Annie Lennox. This powerful collective shaped a generation’s view that traditional gender roles were boring: a first and crucial step toward the ultimate acceptance that different sexual orientations were not only tolerable, but that the lives inhabited by gay, straight, bisexual, cisgender, transgender, and genderqueer people were of value.

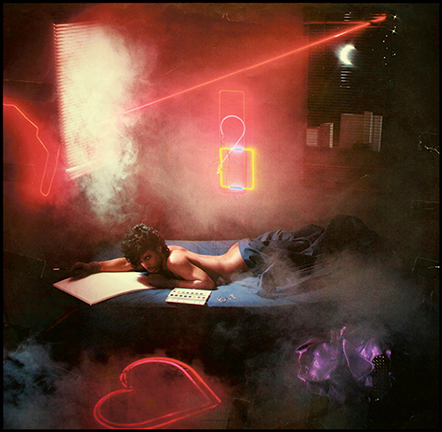

I owned a copy of the double album 1999 in vinyl. I’ll never forget taking the album home, taking the cellophane wrapper off, and removing the record from the cover. The first album had a sleeve, depicting a clearly naked Prince lying in bed on his stomach, sheets pulled down to the middle of his derriere. His back was arched. He started at the camera seductively. He was about to paint something on some sort of sketch pad. The room was smoky; there were neon signs on the wall. Some kind of sex had either just happened or was about to happen in that room. The world stopped for just a moment while I took in the power of that image, the idea that such an image was possible. I was eleven years old. I was years from coming out of the closet, even to myself. Nonetheless, I was never the same.

A few years later, Purple Rain, which would cement him forever as an icon and superstar, was released. One of the hit singles from that album was “I Would Die 4 U,” which opened with the lyric, “I’m not a woman/I’m not a man/ I am something that you’ll never understand.” It’s difficult to explain to someone who wasn’t around in the 1980s just how subversive those words were.

If non-traditional gender roles were depicted at all in popular culture, they were usually psychotic serial killers, and more and more, straight culture was conflating gay men with a disease so strange and deadly that the President of the United States famously wouldn’t utter the word “AIDS” until his second term in office.

Around that time, Prince was singing about the disease. In his 1987 single, “Sign ‘O’ The Times,” he framed his story in heterosexual terms, singing about a woman who contracted the virus from her male lover after sharing an infected needle. It wasn’t the first time that pop stars had referenced AIDS (Band Aid famously sang about the plight of AIDS-afflicted children in Africa in 1984), but when the world was still gripped in fear, every bit helped.

Years later, in 1993, he’d famously become “the Artist Formerly Known as Prince.” While this move was almost certainly tied to his attempts to separate himself from a contract with Warner Brothers (he went back to his real name after his contract ended). But for a full seven years, his “name” was an unpronounceable symbol that fused the traditional symbols for male and female. At this point, I was two years away from coming out myself.

Prince died two years ago. He’s still missed. RIP, Beautiful One. 1958-2016.▼

Eric C. Peterson is a senior consultant in diversity at Cook Ross, Inc.