Beach Houses and Fine Dining: A Beginning

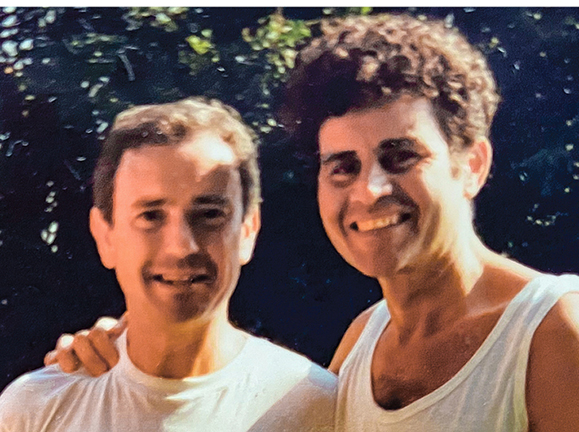

Soon after the 1980 New Year, Steve Elkins and Murray Archibald moved back from St. Louis to DC and into a 16th Street rowhouse apartment. Steve was often on the road, traveling with Robert Strauss who headed up Carter’s re-election presidential campaign; Murray worked for a graphic design firm housed in a gentrifying block on Corcoran Street.

Going to work each morning, Murray says, “I had to push my way through the hookers; it was only a couple of blocks from our house, but it was a huge difference. People had put a lot of money into these houses but hookers were taking their johns into the backyards. The neighborhood association hired our design firm to create a sticker for them: a stylized look of a hooker leaning against a street lamp. It was a square foot and fluorescent pink. They put these stickers on the side of the johns’ cars and they went back to the suburbs.”

After the ill-fated campaign, Steve joined the newly formed McMahon and Associates, a DC consulting and research firm lobbying for progressive policy-related issues ranging from alternative energy to LGBTQ equality.

Joe McMahon, who had served on the staff of Massachusetts Sen. Edward Brooke, met Steve during his White House years. He “organized our very first summer beach house” in Rehoboth Beach,” recalls Murray.

“I’d never been here at all,” Murray said. “Steve had come while at the White House before I met him, just for a weekend.” That spring of ’81, they took a summer share in a house on Norfolk Street just behind the Christian Science Church.

Murray added, “The Blue Moon was open that summer but they didn’t have the bar yet.”

Joyce Felton and Victor Pisapia launched the Blue Moon together on Memorial Day weekend, 1981, on the second block of Baltimore Avenue—a street lined with guest houses but devoid of restaurants or bars, with the exception of the seedy Final Edition.

“Nobody is going to come to Baltimore Avenue,” people told the pair. “If you’re not on Rehoboth Avenue it’s doomed to fail.” But, they didn’t, largely due to their complementary talents and personalities.

First, Victor and the Back Porch

Victor—a graduate of the University of Delaware—taught in Wilmington during the early 70s. After three years teaching high school social studies, he opted for a year of backpacking through Europe. There, the 20-something was “taken with the European café” and the culinary richness of his family’s native Italy. In the fall of 1974, he returned “totally broke, arriving in New York City with 25 cents.”

After visiting family in Dover, “my dad dropped me off at the Surf Shop in Dewey Beach.” Crashing on a friend’s floor, Victor bussed tables at the Dinner Bell Inn on Christian Street, where the Bellmoor now stands. It was one of the few good local restaurants. Lauded for its crab imperial, it was operated by the grande dame restauranteur, Ruth Emmert, who began serving meals to GIs during WWII.

At the restaurant’s milk counter, Victor ran into waitress Libby York, a former teacher who also had just returned from Europe. “We decided this town was boring as bat shit and we needed to do something! That was the beginnings of the Back Porch.”

But, first Victor moved to Boulder. Jobless after several months he hitchhiked back to Rehoboth. On a cold January day, the twosome talked as they walked up and down the beach. “We stopped. She looked at me. 'I really want to do this. But, the biggest thing is I want to do it with you.’ That was the first time anybody ever said anything like that to me. I just immediately said, ‘yes.’ “

From then on it was just planning. Originally to be called the Beach Plumb Café because of Libby’s fondness for the fruit, its location on the back porch of the old Marvel Hotel made the Back Porch more appropriate. Budgeting just a few thousand dollars and recycling salvaged boardwalk lumber and stained glass, they created the new restaurant within the old lumbering structure that had “not a right angle in the place.” All the building was done by Libby’s husband Ted Fisher who was the restaurant’s third partner.

It was also meant to be a simple juice and sandwich bar; it didn’t turn out that way, either. Although the Porch served juices and sandwiches, everything was made from scratch: the breads, the yogurt, the muesli. Victor traipsed local strawberry fields and sojourned for ocean fish, seeking out the freshest local foods.

“I remember being very scared, as we were so young and it was such a big project,” Victor recalled. With scant restaurant experience but a worn copy of Cooking for Crowds, culinary advice, utensils from his Italian mother, and mental notes from the European café scene, Victor would soon invent an innovative menu. This caused a culinary stir on the palates of many a beachgoer.

Libby’s creativity and musicality also created fresh Rehoboth traditions: exhibiting local artwork, hosting live entertainment, providing al fresco dining—and greeting lesbians and gay men. “We didn't care,” one of the first employees said, “most of our staff was gay anyway so there was never any judgement.”

Then, there was Joyce

Four years later, during the 1979 off-season Victor was in New York City on break. He met Joyce at a cocktail party hosted by a gay couple inside a cramped city apartment. Like Victor, she was a restauranteur, managing four restaurants at Macy’s famed flagship store on 34th Street.

In contrast to the mild-mannered Victor, she was—like her mother, says Joyce —“a ball-busting warrior.” The two became “buds” immediately. “He was lovely,” Joyce reminisced. “He talked to me about Rehoboth and his restaurant” and invited her to visit.

A Jewish girl from Queens, Joyce grew up “in the 50s where the norm was for women to wear aprons and be housekeepers. That is not what happened in our household.” Joyce was “raised to be very mindful of people who have less and of women’s rights. I was very mindful of speaking your truth.”

Her role model —“the first feminist I ever met”—was her mother Blanche. She had wanted to go to medical school “but there were no spots for women,” Joyce explained. Instead, she earned a double PhD in marine biology and zoology, becoming a tenured professor. “She was a bad-ass, a warrior for the rights of the underdog,” Joyce spoke admiringly.

As a student, Joyce organized the first Students for Democratic Society (SDS) high school chapter in the country. In the mid-60s, following an armed forces recruitment presentation, she counter-programmed an anti-war film. “I went to demonstrations, the March on Washington, Women’s Rights.”

She also spent a lot of time barefoot and braless in the Village. Then, Joyce enrolled at the University of South Carolina. “I wanted to go somewhere where I was the voice that hadn’t been heard.”

In 1968, she journeyed to Strom Thurmond’s Palmetto State—not as a student but as an agitator. “I wanted to be people’s conscience. I wanted to be an annoyance, a perpetrator, an instigator.” At USC—known as the party school of the South—she found little support for organizing an SDS chapter. “I felt like a stranger in a strange land.”

Rather than studiously attend classes and conform to the school’s dress code, she mostly hung out at the infamous counterculture coffeehouse, the UFO, frequented by sandal-wearing hippies and war-weary Fort Jackson soldiers. Joyce was a “foot soldier” for the Movement, traveling throughout the Carolinas to organize, demonstrate, and agitate.

She also opened up her first business, Big Mama’s Headshop and Holding Company. “I sold rolling papers and bongs—it did not go over well.” Not surprisingly, two years later, this poster girl for the infamous Yankee troublemaker was not so politely asked to exit the university—and the state.

By the time her chance cocktail party encounter with Victor, Joyce had earned a degree in English, opened up a queer-friendly, vegetarian restaurant in Charlotte, married and divorced, and worked in corporate restaurant management.

And Moon Rise

Two weeks after accepting Victor’s invitation, Joyce quit her job at Macy’s and returned to this “under-realized, Mid-Atlantic, southern beach town” to manage the Back Porch Café, “this cool, hippy restaurant serving really good food.” During 18 months at the Porch, Victor and Joyce often spoke about developing a new type of restaurant in Rehoboth.

As Joyce explained, “there was a need, a desire for people to have a place. That was part of the conversation Victor and I had. People were coming from DC, Philadelphia, Baltimore—and they had gay bars in their towns. So, when they would come to their beach, that’s what they wanted. I’d have dinner with these guys and I would see them at the Back Porch. But the restaurant was not designed or promoted to be that kind of spot.”

So, the pair started looking earnestly for a location after Labor Day Weekend, 1980. There was this Victorian beach house they looked at on commercially desolate Baltimore Avenue. When it went to auction, Joyce borrowed money from her parents and Victor sold his interest in the Back Porch along with his car to purchase what would soon become the legendary Blue Moon.

Joyce and Victor were the founding couple of Rehoboth haute cuisine. “We didn’t realize the shit-storm that was going to ensue,” Joyce conceded.

Editor’s note: Read all about that storm in our next Letters edition.

James Sears is the author of many books on LGBTQ history and culture; his forthcoming book is Beyond the Boardwalk: Queering the History of Rehoboth Beach.