Into Each Life Some Rain Must Fall

The recent deluge of rain events in our area has reminded me of Longfellow, and the power of water. We can probably expect more extreme weather in the years to come and along with it more erosion, flooding, and runoff from roofs, driveways, and roads.

While we’re on the subject, the hot topic in landscape circles these days, as evidenced by questions asked at CAMP Rehoboth’s recent Landscape Design event, is Rain Gardens. I thought I would spend some time here talking about their function, their beauty, and the many benefits they provide to us through ecosystem services.

The purpose of a rain garden is to take in the first flush of a rainfall, and allow it to either infiltrate slowly into the ground or be taken up by plants. Rain gardens are usually expected to handle only up to 1” of rainfall. They can be as simple as slight depressions in the ground to more complex, larger areas that are made up of several layers that include underdrains, gravel, filter fabric, and specially designed soils.

The purpose of a rain garden is to take in the first flush of a rainfall, and allow it to either infiltrate slowly into the ground or be taken up by plants. Rain gardens are usually expected to handle only up to 1” of rainfall. They can be as simple as slight depressions in the ground to more complex, larger areas that are made up of several layers that include underdrains, gravel, filter fabric, and specially designed soils.

For an example, a simple rain garden that captures runoff from an 800 square-foot roof requires a depression that is roughly 8 feet by 6 feet in size. The rain garden should be at least 6 inches deep for the depression, unless the soil doesn’t drain well, then it may need to be modified with sand and gravel. In our area, we are fortunate to have well-draining soils but it’s always a good idea to have your soil checked for confirmation.

Now that we have the garden sized and located, let’s get to planting! Part of the beauty of a rain garden is the diverse number of species that call it home. The focus should be on native plants; they are the most successful because they are naturally found in our region and are acclimated to our environmental conditions. Plus, they help sustain our native pollinators and numerous bird species.

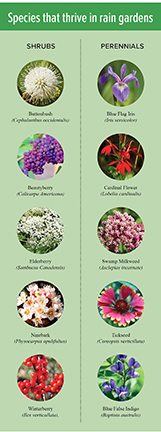

You can also create a theme for your rain garden, whether a monochromatic garden, a sunny summer garden, or a shady woodland garden. It depends on your local conditions and your imagination. Here are some common species that thrive in rain gardens.

Shrubs: Silky Dogwood (Cornus amomum), Winterberry (Ilex verticallata), Elderberry (Sambucus Canadensis), Ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius), Beautyberry (Calicarpa Americana), Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis);

Perennials: Blue Flag Iris (Iris versicolor), Blue Vervain (Verbena hastate), Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis), Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnate), Joe Pye Weed (Eupatorium purpureum), Blue False Indigo (Baptisia australis), and Tickseed (Coreopsis verticillata).

Take note that the lowest part of the rain garden will remain the wettest so plan your species accordingly. Those plants that like “wet feet” should be located nearer the lowest sections and the plants that can tolerate dryer conditions should be located on the edges.

Mulch should be avoided because if a large rain event occurs, it will float and disperse into undesirable areas. Instead, experiment with groundcovers like Coreopsis or Creeping Phlox for sunny areas and Foamflower or Ferns for shady areas.

So, we have the rain garden located and laid out, and the aesthetics of the garden planned. Let’s talk about the benefits it will provide for years to come. Ecosystem Services are services provided directly or indirectly to us that produce life sustaining benefits such as clean air and water, productive soil, pollination, food production, flood control, etc. Believe it or not, Rain Gardens can help with all of these services.

One of the most important aspects of having a healthy ecosystem is that nature is in balance. Where one may see dangerous and nasty insects or animals, predators see their next meal.

I get asked a lot about mosquito control without spraying chemicals. My answer is to plant more native plants that provide habitat and food sources for our native fauna. Our bird population will nest in these spaces, as well as feed their young with insects we find offensive. Plus, not only will the berries of the Winterberry and other hollies feed birds through winter, they are a stunning addition to the garden aesthetically, especially when planted in front of an evergreen backdrop.

And birds are not the only animals attracted to rain gardens. Expect to see pollinators such as our many bee species, moths, and butterflies galore.

Since rain gardens are grown in a naturalistic manner, they will not need to be manicured. Therefore, they require less maintenance. However, no garden is maintenance-free so periodic inspection of the rain garden is necessary.

Part of maintenance can be sharing your plants with friends and family. Dividing large specimens is sometimes necessary for proper plant growth and health, and what is more joyful then sharing your garden with those you love?

I encourage you to install a rain garden in your own back yard, share it with friends, and be a part of helping our planet come back into balance. Let’s garden together! ▼

Eric W. Wahl, RLA is a landscape architect at Element Design Group and president of the Delaware Native Plant Society.